The year was 1994 and I was in the living room of the Section 8 apartment where I stayed with my biological mother, on the outskirts of High Point, North Carolina. I was home alone, parked directly in front of the only color television in the apartment, watching the audience applaud as Nirvana took the stage for their iconic MTV Unplugged performance. The sky outside was overcast on this early spring afternoon; it was two, maybe three days after the band’s magnetic, mercurial frontman committed suicide in a far more grisly fashion than any nine-year-old should think about so obsessively.

I was no more than four inches away from the screen, taking in the imagery of the venue from which the set was being filmed and pretending I was there myself, a practice I would engage in regularly to take myself away from this apartment. The unit itself wasn't really that bad. Spacious enough, central heating so we didn’t have to use kerosene space heaters or boil water on the stove to keep warm during the cold months, fewer cockroaches than other places we’ve stayed.

Whenever my biological mother and I shared this living room, bad things happened. She once punched me in the face so hard it almost swelled my eye shut. She’s thrown beer cans and bottles -- not empty ones -- right at my head. She’s hit me with a crutch and ground my face into the floor with her bad leg padded in the cast. She hurled slurs and profanity-laced tirades at me, summoned protruding welts on my back with her leather belt regularly, blamed me for whatever was going wrong in her life. Such horrors were commonplace for me, to the point where even this early in my life, I thought a lot about Cobain’s suicide. There can’t be anything much worse than living here on earth, I thought.

Listening to the chord progressions, words, and voice of Cobain gave me a great deal to relate to, me finding myself to be a kindred spirit of his before I knew what the term “kindred spirit” meant. He was a flawed, creatively driven, sensitive person, probably a little too sensitive for a world I grew to find deeply treacherous. He seemed haunted by his thoughts, scribbling them down on a page to make sense of them.

The secondhand couch which stretched along two sides of my living room like a half-drawn square was a fair distance behind me as Cobain, Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl, and Pat Smear took the funeral stage heavily adorned with lilies and candles.

Over the years since this taping, I’ve read critics refer to the stage design as “weirdly prescient,” given Cobain’s suicide not even half a year later. But Cobain always struck me, even when I was a little kid, as someone intimately familiar with the idea that death is all around us, death eventually comes for us all. Their cover of the Vaselines’ version of “Jesus Don’t Want Me For a Sunbeam,” with its simple harmonies and Novoselic on accordion, has death squarely at its thematic centerpiece.

“The Man Who Sold the World,” as played by Nirvana, was the first time I heard a David Bowie song. I spent my days after school watching BET’s Rap City before doing my homework, or trying to watch Nick at Nite while my biological mother was blasting LL Cool J and the sharp, chemical smell of crack-cocaine seeped its way underneath the closed door of my bedroom. I acquired the skill of distinguishing the smells of different drugs being smoked at a very early age.

At the time, I didn’t mind when she was on drugs. Those were the only occasions she was nice to me.

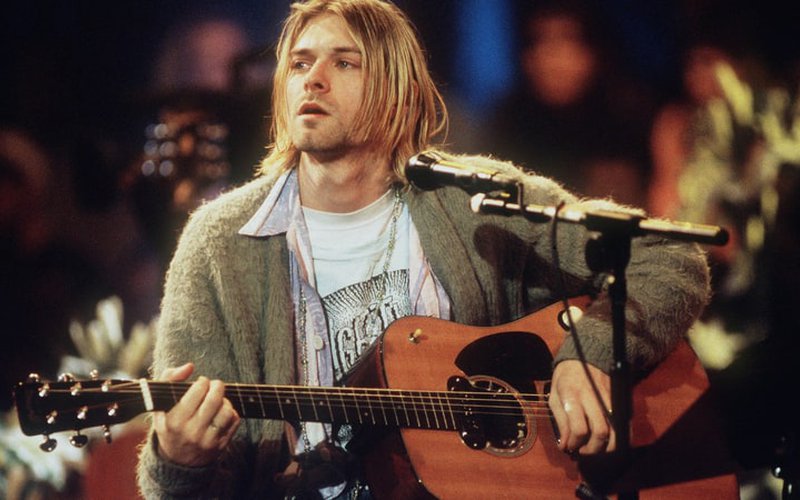

With his piercing blue eyes, lit cigarette, and overworn, vomit-green cardigan, Cobain was the archetypal rockstar positioning himself as the quiet, misfit kid he probably was before he howled his way to worldwide fame and adulation.

I could sympathize with the misfit Cobain likely saw himself as. I in particular was introverted, kind of bookish, pained and afraid from the abuse I had been suffering, the only black guy at a largely white school who listened to alternative rock radio -- long before I became the only black guy at the indie-rock show. I got the impression my aunts, uncles, and cousins saw me as kind of a black sheep, my teachers mostly liked me because I was smart and sweet, but they saw the tumult brewing inside of me.

Not only had Nirvana been my first real exposure to rock music I enjoyed -- versus, say, pretending to enjoy Whitesnake just to feel “different” from people around me -- the music Cobain both selected for this performance and admired in general introduced me to a whole world of music I wouldn’t have been exposed to otherwise. Sonic Youth (though it took me until my early-twenties to really get into them), the Velvet Underground, Beat Happening, the Raincoats. The only two Meat Puppets songs I could name are the two performed here. There was one in particular which took a hold of me that day in front of the television.

“Where do bad folks go when they die?” Every weekend, I would leave this apartment and find refuge in the solace of my grandmother’s place. By this time, after two open heart surgeries, she had moved out of her little house on Montlieu Avenue and into a high-rise for senior citizens. She was a dedicated church-going woman so I was very familiar with the “Lake of Fire” Meat Puppets sang about and joined Nirvana onstage for Unplugged so Cobain could sing about it.

It always fascinated me that the biblical version of hell sounded a lot like living inside of my own head while plagued by the terror my biological mother put me through.

Maybe I had some heavy karmic debt from a past life, and the lake of fire nestled in this Section 8 apartment would rage when my biological mother hit me and told me I was smart for nothing, and I needed to find a way to atone for the sins I didn’t remember committing when I took this body. There was a sense of terror I idenitified with as I watched the members of Nirvana and the brothers Kirkwood make their way through this version of “Lake of Fire,” candle flames swaying along with the music.

The demons that lived inside of Kurt Cobain sounded temporarily excised in the band’s cover of Leadbelly’s “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” the cathartic power of music being made very clear to me in the finale of this life-altering performance. I remember being transfixed as the song and Cobain’s vocals grew more desperate. The howl that ended the song and the taping still sears through my consciousness. That day, I wanted so badly to be shown the precise medium that could help me expel the malice which haunted me from within; a release, a relief from the fiery lake.

Then I remembered Cobain snuffed out his own candle, and wondered if the monsters rattling my bones would still be there after that release, if the catharsis of purging one’s soul was only a temporary fix.

Back in 2008, our intrepid Review Revue Reviewer, Levi Fuller, took an in-depth look at the old KCMU vinyl for Nirvana's Nevermind. In celebration of the album's 25th anniversary, we revisit that blog post below.

Programming like this is made possible by supportfrom donors like you! Help power KEXP!Nirvana's groundbreaking album Nevermind celebrates its 25th anniversary on September 24th, and KEXP is celebrating with a week of programming honoring this iconic album with exclusive interviews, giveaways, and …

On the 20th anniversary of his death, KEXP is celebrating the life of one of Seattle's greatest musicians. On April 5, 1994, Kurt Cobain took his own life but left an indelible legacy for musicians and fans across the world. Throughout the day on Friday, April 4, KEXP DJs are playing a variety of s…