As part of KEXP's National Radio Week coverage, on the KEXP Blog we will be spotlighting some of the stories and personal testimonials given by a variety of radio luminaries in interviews done with KEXP DJs John Richards, Kevin Cole, and Morning Show producer Owen Murphy. These interviews articulately explain the enduring legacy of early independent radio stations, as well as the importance of radio to shape and create a community through shared love of music. In the words of WFNX DJ Kurt St. Thomas, "if you pay enough attention, radio will probably change your life."

As part of KEXP's National Radio Week coverage, on the KEXP Blog we will be spotlighting some of the stories and personal testimonials given by a variety of radio luminaries in interviews done with KEXP DJs John Richards, Kevin Cole, and Morning Show producer Owen Murphy. These interviews articulately explain the enduring legacy of early independent radio stations, as well as the importance of radio to shape and create a community through shared love of music. In the words of WFNX DJ Kurt St. Thomas, "if you pay enough attention, radio will probably change your life."

Vin Scelsa spent nearly fifty years at New York and New Jersey radio stations, gaining fame as one of the most respected DJs on modern radio. Scelsa started his radio career helping the legendary Jersey City station WFMU (then located in East Orange, NJ at Upsala College) flip formats, becoming the singularly free-form station it is today. This was followed by stints at WBAI, WABC (later called WPLJ), WNEW, WXRK (K-Rock), and WFUV (Fordham College's radio station), the station where he eventually ended his career in 2015. KEXP spoke to Scelsa earlier this year, the conversation mostly focusing on his tenure at WFMU and radio in 1970s New York.

In 1967, Scelsa hosted his first show at WFMU, effectively starting his 50-year career in radio. These early days at WFMU clearly helped to foster Scelsa's creativity, the station allowing Scelsa and several other to execute their vision.

By the spring of the following year, a few people and I literally took over [WFMU]. The general manager who had been there threw up his hands and quit because he couldn’t understand what we were doing. A marvelous student named Rand Bullard was hired, along with myself and another guy who was my roommate at the time, named George Black. The two of us were hired at 45 dollars per week. I was the program director, George was the production manager, the guy who made sure all the equipment functioned. Rand Bullard became the general manager, he earned 90 dollars per week. The college left us alone for that summer. We had the first listener drive over that Memorial Day weekend. We had to earn about three thousand dollars to stay on the air for the summer. Up until then, the station had never been on the air for the summer. They would just turn it off, because the school wasn’t in session. It was a club, and the school was totally wasting these airwaves. On the airwaves was a couple of music shows, like guys who wanted to be Top 40 DJs, and then a bunch of educational shows, some of them taped on campus, others syndicated. It was a shame, because everything was exploding in music and culture, and these kids who had this wonderful thing at their disposal didn’t know what it. I felt that I did know what to do with it, so we took it over in spring of 1968.Quickly WFMU gained notice for its programming, a variety of local celebrities or personalities becoming DJs. This included Danny Fields, the famed manager of Stooges, MC5, and The Modern Lovers, and the subject of the documentary film Danny Says. Scelsa remembered one particular encounter involving Fields.

I was hanging around on a Sunday afternoon, and the doorbell rang on the door to this old house. I went downstairs, and there were these four young men dressed like wannabe rock stars. Most of us who worked at the radio station weren’t really hippies, we may have had some of the manifestations, but our clothing wasn’t anything outrageous. These guys looked like magazine hippies. They were just incredible looking. I opened the door, and they said they wanted to see Danny Fields, who was on the air at the time. So I said, "okay, who should I tell them you are?" They said, "We’re the 1910 Fruitgum Company." They were from Cranford or some place, some other suburban NJ town. They were convinced that Danny Fields would fall in love with them and hire them, bring them to Elektra records and make them the next Stooges. I had this vivid memory standing there and welcoming the 1910 Fruitgum Company. They weren’t signed or anything, they didn’t have a record yet, but a year or so later they did. I don’t know what Danny thought of them, but I brought them upstairs, and they hung with Danny for a while.Though Scelsa left WFMU in the early 70s, he soon after worked at WLIR (previously covered as part of National Radio Week), WBAI, and WABC (later re-named WPLJ by Scelsa, after the Mothers of Invention song "White Port and Lemon Juice.") Scelsa reflected on this stint of his career, including one encounter with Bob Dylan.

Radio stations once actually had to promise to fulfill societal demands that required them to do public service and news and serve the community. It was part of the license agreement that they signed. That disappeared a long time ago, that aspect of radio. They were still committed to doing some hours of public service programming, and they did them on Sunday, which was the day they could most afford to not have anybody listening. So they were auditioning a lot of people to come up.Throughout his career, Scelsa repeatedly left stations as the freedoms of the DJs were put at risk. His departures from both WNEW and WPLJ were both motivated by the lack of creative control given to their disc jockeys. In KEXP's conversation with Scelsa, he talked about the difficulty to maintain creative control as a radio DJ, as well as the difficult task of keeping up with the growing multitude of music.There was this guy named One-Legged Terry, that was his name because he only had one leg. I never found out what happened to his leg, but he was a village figure in New York at the time. I think he was the pot dealer for a lot of the jocks on WABC-FM. Terry had a connection to the radical Jewish community in New York, which was probably what the connection to Bob Dylan was, he was likely Dylan’s dealer as well. So Terry got an audition gig to try out for this talk show. He got this guy named Meir Kahane, who was a rabbi in this radical Zionist group and was pretty well known in New York at the time. Kahane was going to come up and be on his talk show, along with some people from less radical and more conservative Jewish groups. They were going to discuss their take on Zionism. Dylan at this time, 1970, was back living in the Village with his family and was interested in his Jewish roots. Terry convinced Bob to stop by to provide moral support.

The audition was done in this big central room, studio 8B or something like that of the ABC Radio Complex in New York. The AM station was one side of the building, and the FM station was on the other side, In the middle was this studio which both stations used. It was the dead of winter, very, very cold out. It came out that Dylan might be making an appearance there to support his friend Terry. So a lot more people showed up to be part of the “studio audience” than you would normally have, which would be nobody basically for an audition like this. It wasn’t even going to be on the air. Because the word had gotten out, secretaries, day time people, non-music people showed up because they wanted to be in the room with Dylan.

I remember coming into the room late in the game, and sitting at this acoustic piano, a baby grand piano. I sat down on the bench. Shortly thereafter, Dylan arrived with this big winter coat and a fur cap, and there was nowhere for him to sit. So he came over and sat with me on the piano bench, so he’s sitting right next to me. It’s 1970, maybe 71, sitting next to Bob Dylan for a person like myself is a very meaningful thing. We never spoke, we never acknowledged each other, he never took off his jacket or his hat. He sat there for about twenty minutes and sat to the show, and before it was quite over, he got up and left with all of his friends, and I started breathing again.

In the 1960s, 70s and 80s, it was relatively in the grasp of one individual to have knowledge of pretty much all of the music that fell within the sphere of what you were interested in presenting on the radio. When I was a young man, it was relatively easy to keep track of everything. One of the things that was beginning to wear me down, was that I could not keep track of anything remotely resembling what I wanted to know about music.While working at K-Rock (WXRK), Scelsa started "Idiot's Delight," the radio show which would eventually become his signature program. During this period, Scelsa remembered seeing the influence of radio DJs in the pervasive 1980s mixtape culture.I do think it’s important for a DJ to program their own show, because every piece of music that you play is a reflection of you and your personality and your dreams and your concerns. I also can see the benefit of having a group with lots of knowledgeable people turning each other on to music, or having a really good producer. That's the name we gave to the other person in the room back in the 80s some time, because suddenly with talk radio everyone wanted to have their version of Boy Gary. You didn’t really need one, because there wasn’t typically that kind of coordination needed on a regular radio show back then. Everybody started hiring producers all of a sudden. So one of the things I did was work with producers who were as enthusiastic and demanding about keeping up with new music as I was, so I would use them, especially when I started getting older and the producers started getting younger, to turn me onto some of the younger bands, which I would then recognize as part of my musical world. I wouldn't know, however, where to find them the way a younger person knows how to find them. A radio show should come from the DJ, it shouldn’t come from a producer or a playlist, but the DJ needs a lot of help these days just to keep up.

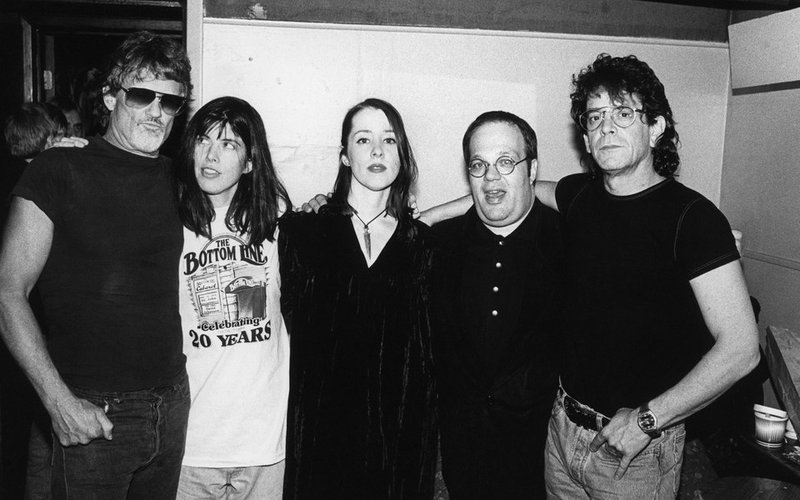

One of the great things that I think filtered over into the main society back in the very early 80s was the idea of people-- regular, ordinary, non-radio people-- putting together mixtapes for their friends and loved ones. People would actually record a cassette of songs that were specifically chosen to speak to someone or somebody about a certain subject. People learned how to do that from listening to the great FM radio stations of the 60s and 70s, where the DJs were doing that, making mix-sets to this individual that was made up of a million ears listening to the radio station.Scelsa retired in 2015, signing off the airwaves with Lou Reed's classic "Goodnight Ladies," which is featured below.

KEXP is celebrating National Radio Day all week long both online and on the air; click here to see all our coverage on the KEXP Blog.

When you talk about independent radio stations that have championed Northwest music, you'd be remiss to leave out Olympia's KAOS 89.3 FM. A hybrid of community radio and college radio with nearby Evergreen State College, KAOS has been a massive force in spotlighting artists outside of the mainstrea…

As part of KEXP's National Radio Week coverage, on the KEXP Blog we will be spotlighting some of the stories and personal testimonials given by a variety of radio luminaries in interviews done with KEXP DJs John Richards, Kevin Cole, and Morning Show producer Owen Murphy. These interviews articulat…

As part of KEXP's National Radio Week coverage, on the KEXP Blog we will be spotlighting some of the stories and personal testimonials given by a variety of radio luminaries in interviews done with KEXP DJs John Richards, Kevin Cole, and Morning Show producer Owen Murphy. These interviews articulat…