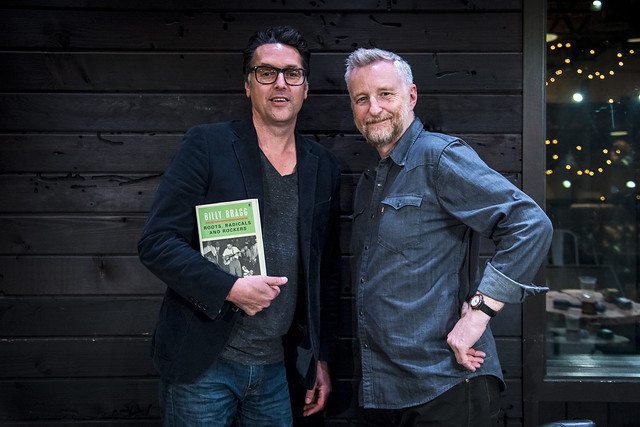

In early October, KEXP was thrilled to host an evening with leftist icon and buck-the-man songwriter Billy Bragg, as part of Songbook: KEXP’s Music & Literature Series. Over the summer, Bragg released his second nonfiction book Roots, Radicals, and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, said to be the first to explore this musical genre in depth.

Bragg sat down with DJ Greg Vandy, host of The Roadhouse on KEXP, to talk about how blues and jazz-obsessed British teenagers and skiffle artists like Lonnie Donegan helped lay the groundwork for the rock 'n' roll counter-culture revolution of the 1960s. Among the things you'll learn in both the book and the chat is that "skiffle" was a slang term for a rent-party where young people obsessed with Lead Belly and New Orleans jazz played records for each other, but over time the term mutated into a British version of traditional American folk and blues. You'll also learn that much more of the '60s revolution was due to kids not getting enough sugar while growing up.

On the eve of the release of Bragg's mini-album Bridges Not Walls (out tomorrow via Cooking Vinyl; read a review here on the KEXP Blog), KEXP shares this exclusive chat. Watch video and read edited excerpts from Vandy and Bragg's conversation below.

Billy, your bio says “you're an English songwriter and left wing-activist whose music blends elements of folk music, punk rock and protest songs with lyrics that mostly span political and romantic themes.”

Who writes this stuff? I'm just a middle-aged guy struggling to remain relevant.

In the first chapter you explain, in great detail, the entire American railroad system.

Part of the quest for the book was to delve into the context of Lonnie Donegan having a hit in 1956 with "Rock Island Line," because most of the stuff that's been written about skiffle has been written in the context of British 1960s and 70s rock stars.

So for most people, they'll get two or three pages that talk about skiffle, always mentioning "Rock Island Line" and Donegan, because it was such an important thing, but generally treat it as a singularity. You know, the amount of knowledge that anyone has about the backstory could be summed up in a request I had when I was just starting to write the book, actually, to do a photo documentary with Aperture Magazine to celebrate the 90th birthday of Robert Frank, the great American photographer. “Would I like to go on a journey across America with a photographer and make a photo documentary?” And I said Yeah. And they said, “you've been coming to America 33 years. Is there anywhere you've you've never been you'd like to go to” I said, “yeah, I'd like to go to where ‘Rock Island Line’ comes from.” And they said “cool. Where's that?” I said “I don't know. Let's go find out.” So you know it was a journey of discovery for me as well.

The whole skiffle scene comes out of a traditional jazz scene that was happening in Britain in the late 40s in the early 50s, which I knew very very little about, and also needed to explain to a rock audience why New Orleans was so important to the trad jazzers. So I had to do a lot of discovery, myself, in the process. But I am very pleased that in the first two pages I managed to mention Abraham Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis.

There are so many questions about this story that I want to ask you because really this is a story about something that's not particularly significant to a lot of music fans, but when you give it context, it becomes hugely significant.

It's really about the context. In some ways, it's more significant than punk, I believe.

"Rock Island Line" gets into the charts in January 1956 in chapter 13 in a 26 chapter book. It's not just a musical context, it's a social context because skiffle is the signifier for the first generation of British teenagers. My father was 15 in 1939 when the war began. He'd grown up listening to English music, eating English food, wearing English clothes. The kids born in 1940 an onward, they had a different upbringing to the upbringing that my father did, a completely different experience. And so the story of skiffle is this story and it also is the story of how the guitar is introduced into British pop music and that becomes the symbol of the generation gap, of the rejection of their parent's culture, of what came before, to play the guitar.

And it's an acoustic guitar. It's always an acoustic guitar because electric guitars just simply weren't available. The symbolism of the acoustic guitar signified that you were refusing to accept the mainstream culture that you were being offered by the BBC, which we could describe as Tin Pan Alley, and that instead, you were interested in music made by people who played guitars.

This is crazy to think, but the skiffle craze lasted basically from 1954 to the 1960s, about five or six years. That's what I think you explain in, I say, the first ten chapters. These early young teenagers who were collectors... there were some key individuals who were just kids in your story who were able to get the 78 and make a small collection, which in turn turned their scene onto New Orleans traditional jazz.

And I didn't know that New Orleans traditional jazz was going to be so prevalent in this book, but that's really where it all begins because the group of teenagers is seeking authenticity by going back to the very beginning of American recording and the traditional jazz of the 1920s.

In many ways, they were very similar to what the Ramones did. The kids that are into trad jazz, which is predominantly jazz made in New Orleans from about 1890 till about 1920, they were rejecting mainstream jazz at the time, which I think we could say was swing, big band crooner. They believed that jazz had lost its essential edge and that the only real jazz was made in New Orleans during this time. And so they were predominantly white students of jazz who were inspired by some the first jazz biographies written in the 1940s, by American jazz fans. They were inspired to go back to basics, as a rejection of the mainstream the same way that the Ramones and Dr. Feelgood went back to the basics of rock ‘n’ roll, guitar rock as a rejection of the mainstream stadium guitar rock in the 1970s. And interestingly, the modern jazzers which were predominantly African American musicians were also reacting against the blandness of mainstream jazz.

In my country, it was that authenticity that they craved. There was a real problem they had, due to a dispute between the American Federation of Musicians and the British musicians union. There was a ban on British artists touring in America and American bands touring in Britain from 1935 until 1955.

And this is very important right here. This is why there is a lack of, I guess, transcontinental communication.

It was impossible for these kids who were into traditional jazz, to see it being played. The only way it was possible for them to learn to play was to see it, and it was impossible for them to do that. All they had to work with were the records, were made predominantly in the 20s, some in the 30s. Now the recording techniques for these records were so primitive, they often only had one microphone in a room. So the original musicians from the 1920s blew really hard to get into the grooves of the record. Now the British jazzers in the late 40s and early 50s who heard these records, had no sense of technique, whatsoever. So they blew the shit out of their instruments, and as a result because of their bad technique, after about 30 minutes their lips were so numb they couldn't play anymore. So in order to not lose the audience, they then put down their brass instruments, picked up acoustic guitars, washboard and a bass and they played what we might broadly refer to as Lead Belly's repertoire. Lead Belly is the greatest folk singer that America ever produced. He could play any style, he could hear a song twice and put it into his repertoire, change it around and make it his. And he was a great songwriter. Woody (Guthrie) looked at Lead Belly the way Bob Dylan looked at Woody. He's an absolute giant in American culture physically and literally. And with regards to skiffle, he was the key character. It was his repertoire, so broad as it was, that it brought a lot of people in, and he really only needed to know three chords in order to do that.

Now Billy, what’s the big deal about “Rock Island Line”?

Well, you got to imagine British pop in the 1950s first. I mean you know. It was all crooners. It was all "(How Much Is) That Doggie in the Window?" It was all British singers sounding like Mario Lanza. In 1955, a guy named Jimmy Young had a hit with a cover of the soundtrack of a Jemmy Stewart film called The Man from Laramie, a cowboy movie. On the sleeve of the record, Jimmy Young is wearing a dinner jacket and a bowtie. That's the only idea of a singer you can get in British pop. Donegan comes along, open shirt, guitar and the way that song just gets faster and faster and faster and faster, there's something really different in that.

It was recorded on the 13th of July in 1954. Now the two other significant things that happened around that time was that. Just a week before on the 6th of July 1954 in Memphis, Tennessee. Sam Phillips was trying to record a 19-year-old truck driver, trying to get him to sing a ballad. It wasn't working out, and he told the guitar player and the bass player and the kid to have a break and while they were drinking some coke, the kid started goofing around on an old blues song called "That's All Right Mama." And when the other two joined in, Sam Phillips said: “what are you doing?” And they said "we don't know," he said, “well, back it up.” And that was how Elvis Presley made his first recording. And the fact that he and Donegan recorded just took eight days apart I think is very very significant.

The last thing that's really significant in this story and what comes next is the fact the rationing of food and clothing in my country ended a month before Lonnie Donegan recorded this song. It didn't end when the war ended in 1945. In fact, there were some things that were rationed after the war that was never rationed during the war, partly because the British government had a responsibility to feed people in Germany. So bread went on the ration, sweets were rationed. There were no fancy cakes. They brought sugar off the ration in 1949 for a week. The tsunami of school kids trying to buy sweets and fancy cakes.. so someone like John Lennon who was born in 1940 will have gotten to the age of 14 without being able to go to a sweet shop and buy what he wanted. So you got to imagine this generation... all that suppressed want, that suddenly is a awaked and by Donegan and then subsequently by Elvis and rock'n' roll, but first by Donegan, so this is a really key part of that context because all those kids experienced it.

You know, Bowie, Elton John, all of them lived during that time of rationing. And there is a sort of sense, I think, that when the BBC refused to play "Rock Around the Clock," which was a hit in 1955, some of the impetus for Skiffle was kids saying "you think you can ration rock ‘n’ roll. Well, I'll tell you what, we're going to get instruments and we're going to play this music whether you want us to hear it or not." It's a very punk attitude, there. And I do think that suppressed urge, stayed with them a long time. Because of that time where they had been deprived, it never left them, that generation. So these are the kids who are deciding that now that what they're trying to do with skiffle and with American roots culture conversely, is they're trying to make the future happen. And the guitar is the key, the means, the symbol to reach the future, to reject what had happened and to make the future happen faster.

This week's Review Revue revisits Billy Bragg's 1984 LP Brewing up with Billy Bragg. See what KCMU DJs thought back in the day.

In solidarity with the students participating in National Walkout Day on March 14, 2018 KEXP played 17 minutes of music, along with voices from the students affected by the Parkland school shooting.

Noel Brass, Jr. sits at the back of Cafe Vita in Greenwood, quietly sipping on an espresso. He's immediately recognizable — it's hard to find a photo of Brass where he isn't wearing his trademark fedora and glasses. It's a rainy November afternoon and I can't think of a better setting to dive into …

After a several year gestation period, Beck finally released his long-awaited album Colors. Written and produced with Greg Kurstin, Colors (out now via Capitol Records) is the most upbeat, relentlessly danceable album he's made in more than a decade. The shapeshifting artist recently talked to KEXP…

With Oh My Virgin Ears!, KEXP's (young) intern Gabe Pollak takes a first listen at iconic albums in music history. With singer/songwriter and author Billy Bragg visiting KEXP's Gathering Space tonight as part of of Songbook: KEXP’s Music & Literature Series, we had Gabe reflect on his first tim…