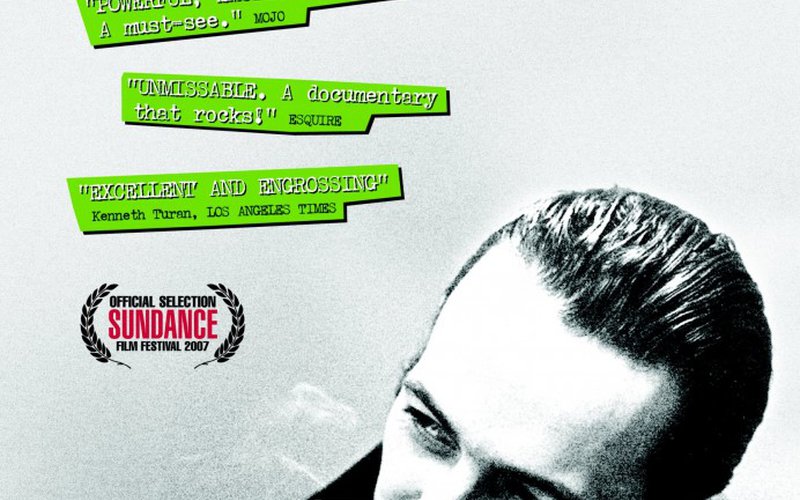

Throughout the history of punk, director Julien Temple was there to film it. His very first short film was Sex Pistols Number 1, a documentary of the band from 1976-1977 that led to the 1980 mockumentary The Great Rock And Roll Swindle, and subsequently The Filth and the Fury. In addition to his filmography, Temple has probably directed some of your favorite music videos, having worked with everyone from David Bowie to Kenny Rogers and even UK pop sensations S Club 7. But it was in 2007 that he released one of his most poignant films to date, Joe Strummer: The Future Is Unwritten, a portrait of the complex, idiosyncratic lead singer of The Clash. The film won the British Independent Film Award for Best British Documentary, and was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival.

KEXP was privileged to chat with this music-obsessed auteur in honor of KEXP's International Clash Day. Thank you to our friends in the Bridgwater Town Council for making this interview possible.

Interview by DJ El ToroTranscription by Alaia D'Alessandro

KEXP: You said that you never had the idea to make a film about The Clash in Joe’s lifetime, nor did you have the idea to make one in the immediate aftermath of his death, so what was the impetus to make The Future is Unwritten? Was it just discovering that footage in your archive or was there something more to it?

Julian: Well, it was also the sense that for some reason there was never a memorial concert or ceremony for Joe, and you know, after a couple of years it seemed everyone who knew him were kind of perplexed that nothing had been done to celebrate him in a big way here in England. So, the idea of doing the film did spring from the idea that we should celebrate this guy. He was such a wonderful person to know and it took a couple of years to just feel strong enough to confront the idea, you know, really focusing on him as the subject. But I can’t remember when we exactly did it, 2006 or something like that. it just felt like the time was right because nothing had been done on a scale big enough to celebrate him. Why do you think that there hadn’t been a celebration like that, do you think that people felt similarly that they wanted to get it right that they wanted to do him justice and thus no one had really had tried to do anything on any grand scale?

I don’t know -- I mean, I think it’s partly that we were also freaked out by the fact that he suddenly wasn’t there anymore. It took people quite a lot of coming to terms with, because he was such a crucial part of the lives of the people who knew him, and when he went, there was a sense of sort-of visceral loss. I think it took people some time to wrap their heads around it. That’s another factor. But I certainly wouldn’t have ever want to stick a camera in his face while he was alive and say, “Let’s make a film about you”.

How did it feel going back and watching that archival film for the first time in decades? It felt good to hear that the sound was okay. That was my main concern. For some reason, I didn’t think we had used... well, they were called Nargra sound tape machines in those days, but I thought we had just shot it on the camera mic, but in fact we did have the Nargra tapes, which made it much better to work with. There was a sense of seeing him as a young guy again that was very moving in a way, because I shot The Clash very early on before they had a record deal. There was a sense when you looked at the early footage that you were seeing a great group destined to be something special. This band when you looked at it, it was very obvious.

In the footage, they seemed more fully formed than you might think if you were to look at a timeline of their career at that point. They seemed ready to go on a grand public scale.

Yeah, and they’d only been going for six months or four months, maybe, when I started filming. They had a mission certainly. Joe wasn’t going to mess around any longer. He had been in his own band and he broke that up in order to do something on a big scale with The Clash.

You filmed both The Sex Pistols and The Clash early in their careers. But I know a lot of music geeks like me think of you as somebody who first documented The Pistols in a great deal. Was the decision to emphasize The Pistols just down to a matter of resources, just in terms of a person can only work on so many projects at so many times, or were there other forces sort-of saying, you need to make a decision? Were people denying you access or anything?

Oh yeah definitely, the manager of The Clash, Bernie Rhodes. After I had been filming them for three or four months, he said, “You gotta make your mind up. You can’t film both of us. It’s either us or them.” I had been filming The Pistols before The Clash, and I had a relationship with them longer, and I also felt at that point, that they were more exciting than The Clash in terms of how they were connecting. So, I stuck with The Pistols, but that meant I couldn’t film The Clash any longer.

That’s infuriating because, of course, ultimately they turn out to be two very different types of bands with two different trajectories. It kind of makes me angry that Bernie would be so small-minded like that.

It was a very kind-of hot house atmosphere in that small punk world at the time. I guess Bernie may have had a series of rivalries with Malcolm. He had been Malcolm’s gopher and assistant and stuff, so I think he was kind of throwing his weight around a bit.

I did like the fact that by using the campfires, and by clearly working your rolodex until it was nothing but tatters, you managed to recapture that hot house environment by bringing in so many different people. As a fan, it was really exciting to me to see like Palmolive and Don Letts talking about Joe’s life along with everyone else.

Yeah, I think there’s something great about the campfire. It was such a thing that was close to Joe’s heart. You know, actually I was in my garden today and cleaning out a place where we used to have campfires with Joe here, and there’s something great about sitting around a campfire. It’s a great leveler. Whoever you are, if you sit with the flames in front of you, you become just another human being, and you know it’s this thing that we’ve always done as human beings. It’s one of those things that hasn’t changed, the fire and the stars, in terms of our experience. Particularly when we were filming people, the fact that the camera was kind-of hidden behind the flames, and people’s attention was taken up by the movement of the flames... it’s a great way of interviewing people. It gets away from that kind-of "grilling talking head" sense of interview. It became a circle of people swapping thoughts about Joe, or ideas they had about Joe, around a very visually wonderful place. It was always the attention that it was a kind of a wake for Joe, this film. You wanted the feeling that he was also sitting there, in his own wake around the fire somehow.

Or in fact, you know, sort of was the fire. Because I think about the way the fire hypnotizes you, and you can also give whatever you are saying over to the fire, and it doesn’t feel like it’s being captured on the film, it feels like it’s going into the fire and the fire takes it.

That’s true, it’s certainly a very fiery presence.

I always appreciated The Clash as a gateway band as they pointed audiences towards other types of music, other types of art, political things that were going on in the world that they might not have known about, and they did this in a very intentional way that a lot of their peers didn’t. How did that sensibility inform the content and the style of The Future is Unwritten?

I think it was very important to Joe that he wasn’t deified as some kind-of distant pop star. His big thing was listening to people, hearing what people said, getting close to people. And that was very much something what I wanted to convey: that he was a flawed, but inspiring human being, like most human beings. So, that was important. I didn’t want to make it a didactic kind-of lecturing thing. I think there’s kind-of a sense of Joe’s belief in social justice. Hopefully it comes through, since that’s very much woven into who he was, but I don’t think it’s an overtly political film in that sense.

I think the social justice element that you’re talking about is definitely very present, and it comes through in a way that young people in particular -- you know, people who are opening up and excited about life -- are ready to receive because it comes through in the music and it comes through in art and in comes through in these things that touch us. You sort of walk it backwards to social justice and racial inequality and prejudice and politics, but you’re starting with “Oh, I like this song,” and taking it the other way.

Certainly the end statement of Joe is incredibly moving in terms of his belief in other people, I think he was very concerned that people do come together to make things better. That does come through, The Clash were a very political band at times, and in some ways I felt like it was a bit too didactic. I preferred The Pistol’s more bleak sense of politics at times, but I just prefer films that don’t have a kind of direct lecturing political message, really.

You mentioned that it was important for you to reflect those flaws, and I do think that we get a sense of Joe’s shortcoming and flaws and things, that he questioned about his own life throughout that life. You do it in a very kind and honest way, which I really appreciated. Was it difficult to get other people to sort-of give you supporting arguments for that, to be honest about their relationships with Joe and shortcomings?

To an extent that was, although if that happened I didn’t really use the material if they were more concerned with treating him like some kind of saint figure. Some people that I did interview were wouldn’t admit in some ways that he did have a lot of contradictions, and was as flawed as the next person, and in fact, I think he made the contradictions within himself the source of the energy for his creativity, so I don’t think he was scared of it. I think in the end, he knew that that’s what made him tick. When people did have something to say that showed him as a rounded human being rather than some distant star light perfection, I tended to put it in the film.

I love that moment where Don calls Joe a coward. He says that Joe shied away from confrontation. I thought that was great, you know, it just made me appreciate and understand him a little better.

Don was a huge friend of Joe’s and I’m sure loves Joe as much as anyone else who knew Joe, so it’s not him dissing Joe, it’s him commenting on the tensions within him that made him tick and made him run as a person.

And you’ve said that The Future is Unwritten is the story of a friendship and being able to highlight the way that Joe did compartmentalize relationships, and did create these divisions at different periods of his life, and sometimes drew on his energy of having clearly delineated those friendships and those periods and then other times letting them blend together. Reflecting on that just sort-of makes the friendships that you’re talking about that much more real.

That was one unusual thing with Joe -- that he could close very suddenly and emphatically a chapter of his life and move onto something else. I found that fascinating when he came down here to live near Bridgwater and Somerset, and this period of the campfire. He was bringing those periods of his life together somehow. There was a great synthesis going on in terms of what he was doing, but also with The Mescaleros and the music he was making down here in Somerset, and I found that very interesting to be around.

What was he like as a neighbor, because as I understand it you weren’t friends for a while and then one day he was more or less knocking on your door.

I think because Bernie had said that I couldn’t work with The Clash there was ill feeling. I think they had thought I had walked out on them so for many years. I wasn’t that close to Joe, but yeah, bizarrely I lived in Somerset where my father’s from, near this town called Bridgwater in the hills before Exmoor. Quantock Hills, it’s called. And one day, my wife’s oldest girlfriend from school called and said, "Can I come and stay with my new boyfriend?" I hadn’t really seen Joe for 25 years properly. I bumped into him having a pee. Taking a piss at a gig -- those bizarre moments I had seen him across America or various weird places in Europe. But anyways, Lucinda turned up and walked through the kind of rose garlanded gate that we have at our house, and this guy that rather looked like Joe came in behind her, and I was like, “Shit, he looks like Joe Strummer” and I think, “Fuck, it is Joe Strummer!” It was the most unlikely thing that he would be the boyfriend of my wife’s friend. Anyway, we kind of looked at each other for a while, and I had been in the middle of making a paper hot air balloon, quite an elaborate thing that was laid out on the lawn. A big hot air balloon for my kids, and I wasn’t doing very well, and he looked at me and said, “Alright, come on, let’s do this thing together. I’ll help you do it.” And so we started doing this together, and it wasn’t as easy as he thought either, so it took us most of the night. We lit a fire outside and we had some wine and we started getting on really, really well. We finally finished the thing as dawn was breaking, and we woke up the kids and lit it up and sent it up into the sky, and it was going up into this beautiful dawn with the birds singing, and suddenly, it just caught on fire, and it was this huge fireball!

Oh no!

And Joe was like, “Ah! I love it, it’s great, so fantastic, I wanna live here!” He just loved that moment, that image, and next thing I knew, he’d bought a house five minutes up the road. Yeah, it was great to be that close, and share a lot of campfires, and explore this area of these hills. Joe got more and more into things in the countryside: the trees and the birds and stuff like that, which I don’t know that he really had known that much about it before, but he had really immersed himself in this place, which was great. He started making music again when he came here. He hadn’t made music, he had lost the kind of edge that he needed to make music, so it was great that he had that last period of creativity with The Mescaleros down here in Somerset in Bridgwater.

I love the fact that you -- no pun intended -- rekindled your friendship during this period when you both were at a later phase in your artistry. You were both dads. You could circle back and pick up the thread, and yet share all these new things, too, that had emerged over the decades.

It was great, and the fact that we did have kids, I think, was another bonding thing. You know, he was a great godfather to my kids. It was a special time, and when he knocked on the door, just the knock was an incredibly exciting sound.

As somebody who emerged out of that original UK punk scene, why do you think The Clash suffered in the UK commercially and critically for intentionally setting out to bring their messages and their music to the United States?

Certainly when the first wave of British Bands in the '60s, when the Stones and The Who kind of abandoned the UK for America, it seemed like people were pretty pissed off, you know. In a way, The Kinks, because they were banned from America, didn’t do that and wrote these beautiful English songs that remain very connected to their audience here in London and the UK. So, you know, I think there was a sense that particularly the second album may have been trying to be some kind of more American style rock band. But for me that was slightly short lived, and the next album certainly wasn’t that. And there was something about the British fandom that if you get too successful, that they get a little down on you, so I think that came into play, but I dunno. I guess the timing of The Clash meant that it wasn’t the first kind of big flash. Punk had gone by the time they really made in in the States, so that kind of music wasn’t as popular as it had been before in the UK. Change happens more quickly. There’s something about American tastes, because it’s such a big country, it’s like an oil tank -- turn it round and it keeps on going for a while -- while as the UK being a very small place, you can be onto the next thing very quickly, and I think The Clash’s response to that was to concentrate more on America, and then develop in a way beyond punk in a way, so I think it was a good thing.

I would concur. You point something out in the film which I had kind of forgotten about. Why do you think that Big Audio Dynamite was accepted so much faster that Joe’s projects in The Clash? Do you think it was just a matter of quality and willingness to put themselves out there, or something else?

I think they were deliberately more in tune with the more fashionable, more commercial music with '80s music at the time than Joe would ever have been. So, I think there was an element of courting whatever would make them popular in a way.

Yeah, I would concur. Especially in the use of samples at a time when that was something that was emerging and very exciting to people.

Yeah, that whole electronic and use of synthesizers and things, you know it wasn’t where Joe was at. He was very much more involved in the rock and roll side of things, wasn’t he. Although later on you know, he did have a period where he was interested in dance music.

Part of what I really enjoy about the film is that you do a very good job of documenting the wilderness years: the film music and earthquake weather and even things that people really gloss over very quickly like Cut the Crap, and you show it some attention and some depth that it almost never gets. Was it important to you as a filmmaker and a friend to dig in, to that and make sure that you didn’t drop the through line?

Yeah, because it was obviously something that was very important to Joe at the time, and I realize that there was some very important songs in there. It was a horribly produced album which Joe had very little to do with the end result of, but some of the songs where you heard the band... that version of The Clash that he had playing them live, there was some great songs in there, some Joe Strummer songs, so yeah, I was determined not to go with the kind of orthodoxy that it was just something that was embarrassing to be forgotten or skipped over.

You frame the film: you anchor it with "White Riot." Did you choose that specifically just because it was the debut single, or were there other reasons that song bookended the movie?

Well, it was partly because it was such a powerful performance from the band and from Joe. That was the first time they were ever recorded at my film school when I smuggled them in on a Sunday night and bribed this old sound guy to let us into the sound stage which was an old '30s Beaconsfield studio, which was a kind of odd Deco '30s recording studio which hadn’t changed since the '50s actually. So this old guy recorded it, and we were in there illicitly, so I had very fond memories of that illegal action, so that may have been part of why I used it. I think it’s emblematic of the beginning of The Clash, that song as well. It’s a great song.

Last one, can you tell me a little bit about Joe’s involvement in the community when he was living in the Somerset area towards the end of his life? It sounds like he chose to take an active role, at least culturally, in certain regards, and I’m wondering if you can give me a little clarity on that.

Yeah, the one thing about Bridgwater is that it has this carnival that’s the second biggest in the UK, after the Notting Hill carnival. This small country town has between 250 and 400 thousand people come on Guy Fawkes Night to celebrate this, which is kind of around Halloween, to celebrate this carnival, to celebrate Guy Fawkes who is the guy who tried to blow up the house of Parliament. The first time I took Joe there, they have these wonderful floats and strange dancing... floats, I don’t know what you call them in America, kind of cars, carriages, and open trucks with these mad constructions, and people dancing, and stuff. But the first song that came past was "Rock the Casbah" with this kind of Disney-esque Aladdin-type thing, and Joe was saying, “Yeah, this was my kind of town.” He did get very involved, particularly in setting up a little art center called The Engine Room in Bridgwater that was partly made possible by Joe doing a benefit gig for them to make it happen, which he did in Bridgwater right at the end. He did one of his last shows, which succeeded in getting the funds for this place to open, which has been a real great thing for the kids in the town. It just gives them access to making films and making music in a place that just didn’t have that option for young kids. So he is very well regarded in the town, because he really cared about it.

Well, that’s a pretty awesome legacy to tack on to another awesome legacy: a conscious decision to inform yet another generation of young people.

I think he was going full great guns at the time. It seemed a terrible time for him to go, because he rediscovered after all his years where he wasn’t quite sure of his direction. He really did seem to be on a roll, and I think that was one of the greatest losses of all, is that we didn’t get to see what he was going to do next.

Like most music lovers I was completely devastated by the suddenness of it, but at least he left us a tremendous legacy of music and art that we can continue to delve into and learn from and share, and I’m really grateful for that. And on that note, I’m gonna add that I’m really grateful for your body of work, because you have been there with me pretty much throughout my entire adolescent and adult life, watching and listening to music, and I had been thinking about you quite a bit since the passing of David Bowie and sort of realizing that you have been there with me throughout my life, so thank you!

Well, that’s very nice of you to say, and great to talk to you about Joe, because he continues to inspire me and there’s not that many days that go by without me thinking about him, too.

Acclaimed drummer and musicologist Jon Wurster talks to KEXP about his first-ever favorite band, The Clash.

Citizen University is committed to encouraging civic literacy, engagement, and activation. We talked to Ben Phillips, Senior Program Manager for Citizen University, to learn more about the organizations mission, their unique approach to community building, and how people can get involved locally.

The station "where the music matters" is paying tribute to the "the only band that matters" this Friday on the air, but the party doesn't stop there: on Saturday, February 6th, The Skylark in West Seattle hosts an International Clash Day Concert to benefit KEXP's New Home! Seattle favorites Polyrhy…

Icelandic hip hop collective Reykjavíkurdætur ("Daughters of Reykjavik") are a force to be reckoned with. A huge group of seventeen women, they work together to create songs about topics ranging from sexual politics to political ones. During KEXP's broadcast at Iceland Airwaves last year, they play…